Tom Stienstra endured outdoor risks but cancer made him face ... - San Francisco Chronicle

The first hint I should have gotten that the sun could kill me came 40 years ago on the flank of Mount Whitney. My brother Bob and I had climbed a 2,000-foot snow field to reach 13,645-foot Trail Crest junction, perched at the foot of Whitney's 14,505-foot summit.

"Your face is so red, you look like a boiled lobster," Bob said as we finished the climb.

"The sun reflected off the snowfield and gave you a double dose," said my old friend, Jeffrey Patty, a wilderness photographer and a partner across 25 years and 10,000 miles of hiking, camping and fishing.

Back in the mid-1980s, few of us worried about sun exposure. Some young people would coat themselves with baby oil and lay out tanning for hours. In the high country, or on the bay or ocean, few applied sunscreen.

Today, we know long-term sun exposure can cause melanoma, or skin cancer, which can metastasize, invading vital organs and even your brain.

It's a lesson that at 68, after a lifetime as an outdoors writer, I have learned the hard way.

In August 2021, after an ambitious few days of hiking, biking and mountain climbing with my wife Denese, I developed a persistent cough. Within a few weeks, a chest X-ray had revealed a series of tumors in my lungs. Two weeks later, Stanford Medical Center radiologists found more tumors in my brain and throughout much of my body.

Over the next six months, Stanford Professor of Neurosurgery Dr. Steven Chang, and a team of 15 specialists would complete four craniotomies to remove tumors in my brain, set up a blood drain in my head, remove additional fluids, and perform CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgery procedures to six tumors, targeting radiation at any cancer cells they could find. Doctors used staples to close the surgical sites, making my head resemble a network of train tracks. Some friends visiting me called me "Zipper Head."

Dr. Sunil Reddy, a cutaneous oncology specialist, scheduled immunology infusions every two to three weeks to jump-start my immune system and attack the cancer that had grown in my lungs, liver, lymph nodes and many other spots.

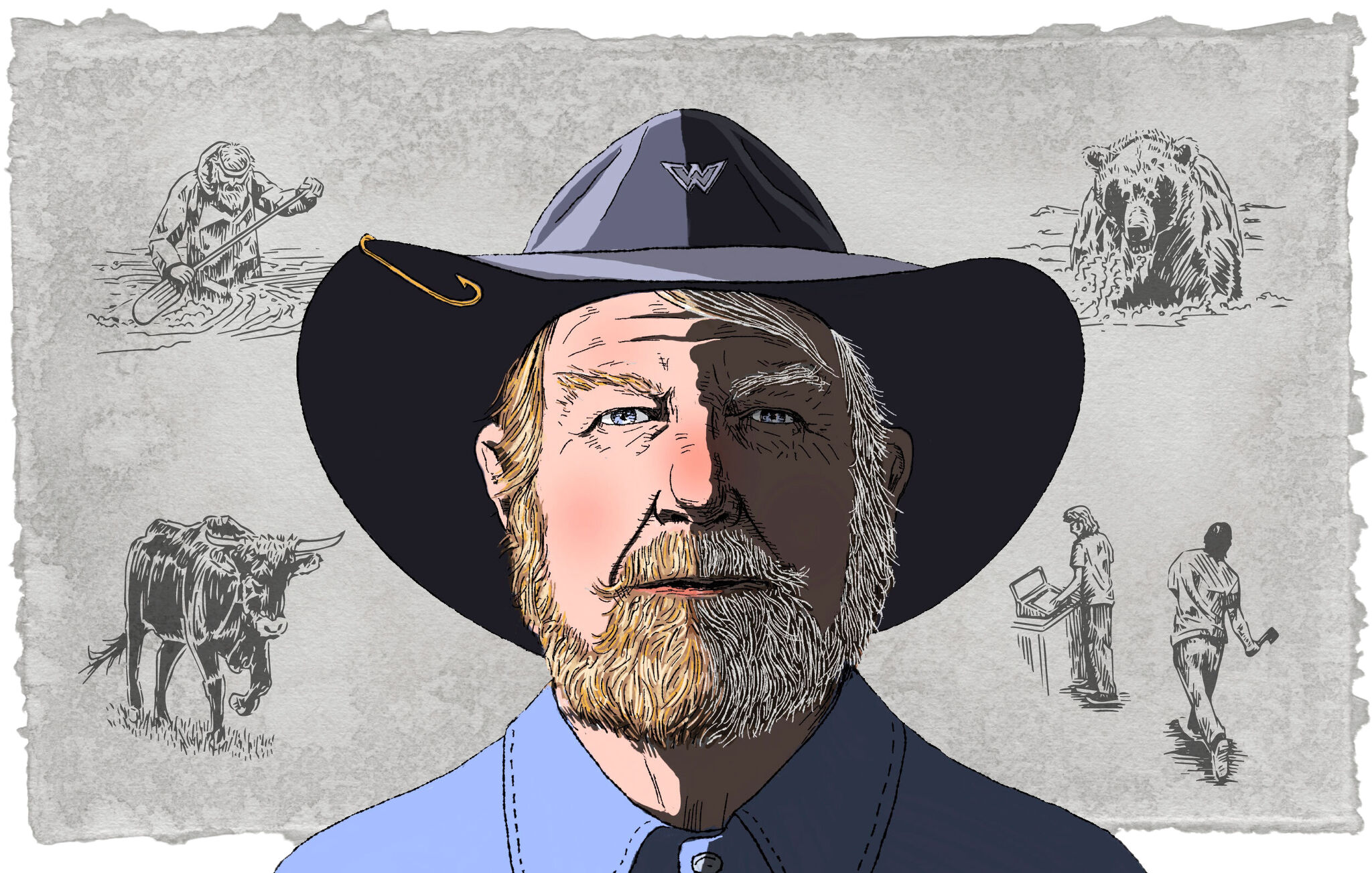

Over the first six weeks of treatment, the infusions turned my grayish-brown hair and beard a vivid white. David Zimmer, a pal since age 13, started calling me "Woodrow" and "Captain" after Capt. Woodrow Call (played by Tommy Lee Jones) in the TV Western mini-series "Lonesome Dove."

"Yes, your hair turning white is related, and probably a good sign," Dr. Reddy said.

In just two months, my body, once trained to bench press 250 pounds, became thin and frail; doctors gave me a lift limit of two pounds. My weight shrank by 60 pounds, hitting a low of 157.

The first two brain surgeries were performed as emergency procedures. They made my vision go haywire. When I woke up in the ICU, the room appeared sideways. When Denese visited, I could see only the upper half of her; she looked as if she were gliding around the bed. My blood pressure rocketed. Nurses seemed petrified, worried I was headed for a seizure or stroke. I tried to stay calm but largely failed. My breathing became short and shallow. I worried about going blind.

I would later learn that the surgical team had given me about a 50% chance of surviving that first week.

"You almost died twice on the operating table," Dr. Chang told me later.

I felt so humbled in the face of death. I prayed to stay alive, both for a chance at a restart on life and for time to get my house in order. For so many years, my goal had been to take part in every activity imaginable in the outdoors, share those experiences through my writing and try to be the best at doing it. As I recovered from my third brain surgery, I received a text: The Outdoor Writers Association of America had given me its highest award for career achievement, making me the first outdoors writer from California to win in the organization's 93-year history.

Yet that day in bed, my body failing, uncertain if I would survive the week, I didn't care about awards. Instead, I found myself regretting every mean thing I'd ever said, lamenting having given the time of day to anybody who had crossed me. All that mattered, I realized, were the people I cared so deeply for: my wife, my family and friends, and those blessing me from afar.

Surviving adventures, close calls

"So, this is how it all ends."

As an outdoorsman for more than 40 years, there was no place I wouldn't go, nothing I wouldn't do, no matter how long it took or how great the challenge. I would spend as many as 200 days a year in the field. Along the way, I survived dozens of close calls – in canoes, rafts, airplanes, in the wilderness on and off trails.

Early on, I learned that risks in the wild often arise without warning. About 25 years ago, I took courses in firearms and self-defense at Gunsite Academy in northern Arizona. There, Il Ling New – one of the top female self-defense instructors in America – taught me the First Commandment of Safety: "Everyone thinks they will rise to the occasion. What happens instead is that you default to your level of training."

So over the years, I always sought the best training before I explored a new area or activity. With that approach, I became competent in 25 areas of outdoor sports, including mountaineering, all types of fishing and scuba diving.

In the outdoors, though, surprises are a constant. They are one of its great appeals, but often its greatest hazards, too. "You never see it coming," we often say.

Like the time I was flyfishing on the Moraine Creek in Alaska's Katmai National Park in the mid-1990s. I'd just released an 8-pound rainbow trout, my lifetime best trout on a fly rod, when I sensed a shadow. Looking up, I locked eyes with a 1,000-pound grizzly bear at the top of a bluff about 40 yards away. It charged down the bluff, directly at me in the river. "So, this is how it all ends," I remember thinking.

In the water, thigh deep, I backed off cautiously. At the same time, I watched the big bear swim slowly across deep water to get to where I'd been standing. That gave me a chance to create more distance. The big bear stopped right where I'd been fishing, rose up high and then swirled in a circle in the river, slapping the water with its giant paws. It let me withdraw, but its message was clear: He was letting me know that this was his fishing spot, not mine.

Another time, in the early 2000s, armed with a muzzleloader I had built, I was hunting for wild pigs near Mill Creek above Black Rock in the Ishi Wilderness in remote Tehama County. I spotted a rare wild cow about 100 yards away. I fired my rifle near him to try to scare him off, but he just stood there. I decided to name him BDS, for "Big, Dumb and Stupid."

Two hours later, though, BDS emerged in front of me as I rounded a large rock. He charged, his horns sharp as spears. I dove to the side and he missed plowing into me by inches.

I've had dozens of encounters like these, near misses that make for great campfire tales. But looking back now, I realize those experiences have given me a humbled outlook on the world, and a deep respect for nature.

And sometimes, I've learned, both in the outdoors and in everyday life, you just might need a guardian angel.

On a cold late November day in 1985, my brother Bob, our dad Robert Sr., my cousin Lloyd and I ventured out to Hills Creek Reservoir on the west flank of the Oregon Cascades for a canoe fishing trip. Trout often bite on frigid days as if it's their last supper before winter takes over.

As we arrived, we saw that ice had started forming in shaded, wind-protected coves along the shore. The air was crisp, so we bundled up in layers.

After we launched my canoe, I took the stern, steering and helping power the boat. The others took turns getting on board and paddling at the bow. After an hour or two on the lake, Bob and I paddled to shore. I dropped him off and began turning the boat across a large cove to pick up Lloyd on the far shore. I used a technique called the "J-Stroke," more properly the "Ojibwe Stroke," I'd been taught. It allows the stern paddler to keep the canoe in a straight line without having to shift the paddle to the other side, and in the process, drip water in the boat.

Yet immediately, the canoe felt wrong. Without another paddler up front, the boat was stern-heavy. The bow rose up, and a strong Ojibwe stroke flipped the canoe.

The water was icy, maybe 34 to 36 degrees. To my brother on shore, I immediately appeared disoriented. He said I flailed around aimlessly and incoherently for more than five minutes. To me, it seemed like just 15 or 20 seconds.

Somehow, I was able to pull myself atop the flipped canoe, to use it as a float under my chest. I thought I could kick-paddle my way to shore, but my legs were numb and unresponsive. That's why life preservers can't always save you in icy water. To Bob, it looked like I might have gone down for the count twice.

The truth is, the water stopped feeling cold. I actually felt good, even euphoric. I found out later, from others who had survived near drownings in cold water, that this is a feeling you can get just before you go down for good.

Bob stripped, jumped in and swam out to me. I tried to wave him off, to shout, "I'm fine, don't worry about me," but no words came out.

As Bob grabbed the bow of the upside-down canoe, he let out a deep-throated groan of anguish from the cold water. Through sheer force of will, he paddled us to shore.

After Lloyd and Bob hoisted me onto land, my legs still would not function. "I'm in worse shape than I thought," I remember thinking. As hypothermia set in, I just wanted to sleep.

Bob, who had served as an assistant medic and radio man on the front lines in Vietnam, slapped my face in an attempt to keep me alert and fed me trail mix and jerky – knowing that digestion can help create warmth from within. He and Lloyd pulled off my wet stuff and dressed me in Bob's dry clothing. Within an hour, I came to.

Bob and Lloyd flipped the canoe right side up. Inside, trapped beneath the yoke, was a paddle, the fishing rod that my late grandfather had given me when I was a boy, and a blue rubber dog bone that my dog Rebel had rebuffed.

That evening, over dinner at a pizza parlor, Bob said that finding those items still in place was a message.

"It means you're meant to paddle and fish again and have a long, happy life with Rebel," he said. For the rest of my life, I decided, I would bless every trip on a boat with that blue rubber dog bone.

I told Bob he had saved my life. He smiled, and reminded me that the rod my grandfather had given me survived the accident too. Maybe, he said, "we had somebody looking out for us the whole time."

It began with a cough

"I don't know how right now, but somehow I will beat this thing."

My cancer showed up in the summer of 2021 in a far less dramatic way, in an annoying cough.

That August, in three days over a week's time, Denese and I had trekked a mountain stream, biked 15 miles and climbed Mt. Shasta off trail up to 10,000 feet. And I began to cough. We blamed it on particles in the smoky air from wildfires in the region. A trip to my doctor led to an extensive check-up. After listening to my heart and lungs, two doctors found no issues. "I wish all my sick patients sounded like you," one said.

The next week, in search of clean, clear air, we ventured to northern Oregon. Yet after climbing near the brink of Multnomah Falls along the Columbia River, the coughing continued. Back in California, we returned to the doctor's office. After tests again revealed no issues, Denese, who has a healthcare background, suggested we get an X-ray of my lungs at a local hospital.

It showed a massive tumor in my right lung, plus several smaller tumors.

"Damn it!" she said, "This wasn't supposed to happen. You owe me another 30 years." When we were married in 2015, we made it a goal to have a dream life together – and for each of us to live to 100.

"I don't know how right now," I told her, "but somehow I will beat this thing."

The X-ray, though, was devastating. It just made no sense. Most life expectancy estimates are based on genetics, and my mother, just like Denese's, is in her 90s, healthy and vibrant. There is no cancer in my family history.

I wondered if I missed a clue in the many headaches I had had. Over the years, I had tried treating them by taking Excedrin daily and wearing a mouth guard to keep from grinding my teeth. For 30 years, I always mentioned the headaches at annual check-ups, but no doctor thought to order an MRI exam of my brain.

Otherwise, there'd been no sign of serious illness. Denese and I eat right, sleep right and are active and fit; we've hiked and biked tens of thousands of miles together. We both loathe even the distant scent of cigarette smoke. Because I'm a pilot, I've had my blood drawn and checked for a series of benchmarks every two years for most of my adult life.

I also had followed advice that my longtime friend and fishing partner, Dusty Baker, gave me 20 years ago. Dusty, the former Giants manager who won the World Series last year with the Houston Astros, told me to have blood drawn every year "and have it tested for everything imaginable."

"You need to have a baseline," he said. "That's how they catch the bad stuff. One day a number comes in out of whack and they know what needs to be addressed."

With hospitals filled with COVID patients that summer, it was difficult to find one that would admit me. A longtime friend and mentor, philanthropist Gary Bechtel, once told me if I ever need medical care, to let him make a call for me. That's how I got into Stanford Medical Center.

Doctors there first planned to do a biopsy on the cancer mass in my right lung. Instead, after observing me and conducting a few tests, they put me in a wheelchair and sent me for a series of brain scans. About 2 or 3 a.m. that night, after CT, PET and MRI scans, they told me that I was full of cancer. It was the first I knew my life was a cancer timebomb.

A neurosurgery team specializing in brain surgery was put on emergency notice. Doctors put me on meds to prevent a seizure and had nurses watch over me. Only one visitor, my wife, COVID-free and vaccinated, was allowed in my room.

The idea of my brain and body full of cancer was petrifying. At first, we didn't know what kind of cancer it was. But within a week, doctors determined it was melanoma, likely from the extensive exposure to the sun earlier in my life.

Dreams and data bring hope

"He's got to be the most stubborn guy out there."

I've been lucky in life to make great friends, most of them regular folks, some well-known. After my initial brain surgeries, I was visited in my dreams by some of them who had passed.

One was my longtime hiking buddy Jeffrey Patty, who died of cancer years before. Country music "outlaws" Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard also showed up. We had hit it off before they became famous, and over the years, we found times to connect. In my dreams they were happy and light, so unlike their personalities in life. And they would offer advice.

In one dream, Jeffrey told me to go to Apple Jack's bar in La Honda, order a Pabst Blue Ribbon, tip big, then watch for a sign from him. So, on a weekend before a Monday surgery, Denese drove us to Apple Jack's and I complied with Jeff's instructions. If there was a sign, though, it was too subtle to discern.

Those dreams, though, helped me hold onto hope that no matter what was ahead, life or death, I would be OK.

Friends and family helped, too.

One of my best friends, Steve Griffin of Michigan – an outdoors writer, author and my muse – wrote me a passionate letter. It was important for me to accept the Outdoor Writers award, he said. Hundreds of writers across America dream of such an honor. Grif is one of a handful of people I listen to. Still, it took me two months after I received the package with the plaque before I opened it.

Some days, I'd be taken outside in a wheelchair. There would be Bob, sitting on a bench, often with a book, having waited for hours hoping for a few moments to connect. One day Dr. Chang had a chance meeting with him. "How's my brother?" Bob asked.

"He gave us some challenges, but he emerged," Dr. Chang told him. "He's got to be the most stubborn guy out there."

Two weeks in, after two brain surgeries, a blood drain and CyberKnife radiosurgery procedures to six tumors, I received the first of several texts I would get from Dusty. Over the course of his time in San Francisco, we became friends and fishing buddies; in my boat, casting for bass from the bow, he is like a Golden Retriever on point, the most focused and intense angler I've ever had aboard.

Dusty was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2002 while he was managing the Giants. Last winter, during a trip to Kauai, he contacted me: The key to beating cancer, Dusty wrote, is to have great trips to look forward to. Your body will stay alive to make sure you experience them.

"Keep your goal in your mind, body and soul," Dusty said. "Keep living and enjoying every moment."

Throughout my career, many readers who had received diagnoses like mine sought me out. Some asked if I would share time with them, perhaps take them on a last special adventure, or just provide advice on my favorite places to go. I always did my best to help them, even taking some on flights in my plane. I'd never once thought, "This could happen to me."

One man, named Al, who would die of ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease, told me: "If I'd known I was going to get something like this, I would have done a lot of things differently in my life."

I've heard almost the same thing from every person I've connected with who has been diagnosed with cancer. From early in my career, it made me determined to leave no dream behind. Staying true to that philosophy sometimes drove my supervisors crazy: I often refused to take part in any work that was not part of that dream.

I've come to learn that there are a lot of people in the cancer club – and a lot of survivors.

The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) reported in late 2021 that more than 18 million Americans have a history of cancer, "yet more people than ever are enjoying more prolonged and more fulfilling lives after receiving a cancer diagnosis." Cancer death rates declined by 2.3% between 2016 and 2019, according to the AACR.

The association also reported in 2022 that the FDA approved eight new anticancer therapies, including for melanoma. These are immunotherapy regimes, where blood is drawn for analysis every two weeks to a month, then followed, a day or two later, with intravenous infusion. Each session takes about an hour to complete; the drug provides the body with components to boost its immune response. Stanford oncologist Dr. Reddy ordered an IV infusion of Nivolumab every two weeks, and explained that MRI scans of the brain and PET scans of the body can assess if treatment is helping diminish and beat back the melanoma cancer.

Health, quality and length of life can also be enriched by many other factors, Dr. Mauro Janoski, my oncologist at Dignity Health/St. Elizabeth Hospital in Red Bluff (Tehama County), told me. I've been receiving immunotherapy there for the past several months, and as this year evolved, doctors doubled the dose but reduced the infusion to once a month. "Fitness, weight, not smoking, eating right, sleeping right, attitude and hope can all affect your health and how long you live," he said. A network of loyal friends you can trust 100% is also vital, he said. A patient and loving spouse can turn your life around, he said.

Patients who get the type of immunotherapy infusions I've received have a range of response rates. According to several medical facilities that perform them, about 20% to 50% survive over a 10-month period. Those starting with good fitness, no bad habits and good genetics do the best.

At a medical conference in fall of 2021 in France, one study reported that 20% of cancer patients using immunotherapy infusions, often in combination with chemotherapy, survived five years after the original diagnosis. The goal, at Stanford and other facilities with cancer treatment centers, is to find ways to harness and boost the immune system to fight cancer rather than using chemo regimens to try to kill it.

In early winter a year ago, the first PET scan found 10 tumors in my liver, as well as others throughout my body. Six months later, another PET scan found no tumors in my liver. Many others were all but gone. Through it all, though, I sometimes felt like I was disappearing, too. Last winter, my weight dropped below 160, my hair turned white overnight, and my face and chest became almost skeletal.

For good luck during one immunotherapy treatment at Stanford, I wore a personalized sweatshirt I got from Jacqueline Douglas, captain of the Wacky Jacky sportfishing boat at Fisherman's Wharf, with my name embroidered on the right upper chest. Another patient walked by three times, staring at me, then finally stopped.

"Where did you get that sweatshirt?" he asked. "Did Tom Stienstra give it to you? I met him at a sports show and he looks nothing like you."

Still, after six weeks at Stanford, I was allowed to go home. I was sick but alive, and Denese became my nurse.

Once home, though, she had to take me to the emergency room to be treated for two infections, and doctors ordered me on oxygen full time. It took another month to emerge from that encounter. When oxygen tubes were removed, I began to feel like I just might survive.

A celebration, then a shock

"That is just scar tissue."

Following Dusty's advice, Denese and I scheduled a trip to Kauai and planned other landmark-type moments for the months ahead. That helped me make it through the year. Over six months into the summer, I added 40 pounds and started regaining my strength, along with my vision and voice. As I built my strength, I went from a wheelchair to a walker to a cane, and finally began walking on my own.

"More like staggering,'' Denese remarked. "You moved like a zombie in 'Night of the Living Dead.' "

We decided it was time to celebrate. In late August, Denese and I hosted a party for friends and family who had supported us during my ordeal. We called it "Never Say Die." It was a dream evening. At one point I got to play lead guitar on a few songs with Northern California guitar legend Jimmy Limo. Many of the 75 folks at the celebration congratulated me for "beating cancer."

But just two weeks later, the afterglow of the party dimmed. A radiologist studying a new MRI scan of my brain identified two small spots that looked like white kidney beans. He believed they were new tumors forming at sites where tumors had been removed.

I felt a deep pang in my gut. Suddenly, the battle was back on. My planned trip to Kauai looked doubtful. We scheduled a meeting with Dr. Chang, thinking we would need to arrange another surgery, more CyberKnife treatments, or both.

Yet as the meeting started, Dr. Chang appeared light and happy, even effusive. He had reviewed the MRI images and read the radiologist's report. "Everything looks great," he said. "The areas of the surgeries look significantly better from the last MRI."

Surely there was still bad news, we thought.

"The radiologist identified two new small tumors," Denese said. "What about that?"

"That," Dr. Chang said, "is just scar tissue forming at surgical sites from your prior treatments."

In one sentence, I had my life back. What had felt like a pile of bricks on my back lifted instantly.

Dr. Chang showed us my brain scans, pointing out the small white shapes that had been identified as tumors.

"Nobody knows the inside of Tom's brain like me," he said with a grin.

Denese's face was filled with astonishment. The moment felt like a scene from "The Twilight Zone."

A first brush with death

"You ever notice how a lot of strange things seem to happen to you?"

During all the time I spent in a hospital bed, I noticed that the mind-bending headaches I had suffered for years had stopped. Doctors weren't crystal clear why this happened, but my head felt free of pain.

I also had time to think and reflect. I thought back on all the close calls I'd had in my life: the grizzly bear, my near-drowning, the wild cow, endless others. It seemed miraculous I had survived those.

My mom, Eleanor, now 95, once took me aside. "You ever notice how a lot of strange things seem to happen to you?" she said. That comment has always made me laugh.

Surviving the cancer in my brain and throughout my body, I figured, might take an actual miracle. Like the one that happened decades before, when my brain came under another kind of attack.

I was just 21, working my way through college at San Jose State. I was earning $5 a story from several peninsula newspapers I wrote for, and $10 a pop from the Associated Press, so I took on several side jobs. One was working part-time at a gas station on El Camino Real in Menlo Park.

Five times a week on summer evenings, I staffed the place alone. On the night of July 16, 1975, at 10:03 p.m., I was closing up shop when a guy came up behind me and hit me in the head with a hatchet. His mission: kill me and steal the money in the till.

The blow first felt like my head was a soft melon splitting apart. My skull vibrated as if I were standing in the center of a giant gong echoing around me. I remember falling, but somehow, on the way down, deflected a second whack that hit me in the back. In the process, I turned my head and got a split-second look at the face of my attacker. In the crisis of the moment, my brain was working so fast that everything seemed to be in slow motion. Though I locked eyes with the attacker for just a moment, it felt as if I'd stared into his face for hours.

My shirt was soaked red. A 6-foot-wide pool of blood formed around me. I was bleeding out on the floor, I realized. Before I passed out, I remember thinking, "This could be it."

Paramedics arrived and put me on a gurney. Menlo Park Police later told me I had called them, including giving a description of the perp, but I didn't remember doing that. What I do remember, still vividly, is that as the paramedics carried me to an ambulance and tried to stop the bleeding, I stared up, and looking down at me, I saw a group of 20 or so people. They were gathered around me in a half circle, silhouetted and backlit by the bright lights of the gas station behind them.

Later, a co-worker who lived next to the gas station told me that no one else was around when the paramedics reached me, and that I was unconscious when they carried me to the ambulance. I've always wondered if maybe I had glimpsed figures from another dimension, waiting for me to cross over.

On the way to Stanford's hospital, the paramedics stopped the bleeding, saving my life. On arrival, I was transported for X-rays, brain scans and treatment, plus a blood infusion. Once doctors were convinced there was no additional bleeding in my brain, they sewed up the canyon in the back of my head.

The man who attacked me, Frank C. Carrasco, had a rap sheet three pages long. He was arrested for the attack six months later. In San Mateo County Superior Court, he was convicted and sentenced to five years to life in prison, but was released after 2 1/2 years. For years afterward I kept track of him, and even kept my camping hatchet under the seat of my truck.

Though many suggested I go after him, including detectives who gave me his address, I'm proud I never sought revenge. Over the years, alone at camps with my dog, Rebel, I often thought about it. But I decided my life was too good, a dream life at times, to do anything to violate it. Still, when Carrasco died a few years ago, I felt a great relief.

For many years after that attack, I suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, and Rebel was my service animal – though I didn't realize either at the time.

A therapist with an expertise in PTSD, Stan Drucker, helped me learn how to avoid the meltdowns I had by stopping triggers that can line up like a row of dominoes before tumbling into an implosion. After a meltdown, I might react by flying to Canada in my plane, hiking a few weeks on the Pacific Crest Trail, bailing with Rebel to camp solo or driving somewhere for 12 hours.

Sometimes I'd go six, seven months without setting foot in an office. When I finally did, I could only deal with the feeling of the walls closing in on me for an hour or two, and then would have to bail again to my truck or airplane and hit the wide-open spaces. Some people thought I was crazy or on drugs. Nope. Fortunately, I was blessed to work with editors who realized I wasn't crazy, just "a wounded brother," as Waylon called me.

These days, my only job is working on beating my cancer. In mid-December, a blood test showed my white blood cells were measuring normally, an indicator that my immune system was again firing on all cylinders. Just before Christmas, Dr. Reddy provided his unique perspective. "People can live five years (after being diagnosed), and maybe after five years you might be cured," he said. "Certainly, you could have 10 years."

My doctors remain concerned about the potential for inoperable brain tumors; immunotherapy doesn't combat brain cancer. That is why I have MRI exams of my brain every three months.

Ten years won't get me to 100. But Denese and I are still planning on living a dream life.

Because if I have learned anything from this close call, it's that in the end, love is all that matters. Like Dusty told me: Think about your priorities, what is important and what is not. Make time to connect with the people who matter most, and regardless of your religious outlook, stay spiritually connected.

I've also learned that my life of hiking virtually every day, along with camping, boating, fishing, riding bikes and flying, keeps me fit, builds my immune system and provides something I can always look forward to. And Denese and I now have a new partner in our travels. Last Saturday, we adopted a newborn Bernese mountain dog. Just like us, this puppy will need to go for a few walks every day.

Tom Stienstra is The Chronicle's outdoors writer emeritus. His latest book, "52 Weekend Adventures," won second place in the nation for outdoor book of the year from the OWAA.

Comments

Post a Comment