Pembrolizumab Yields Clinical Activity in Bladder Cancer Subtype

Vaccines Could Be The "next Big Thing" In Cancer Treatment, Scientists Say

The next big advance in cancer treatment could be a vaccine.

After decades of limited success, scientists say research has reached a turning point, with many predicting more vaccines will be out in five years.

These aren't traditional vaccines that prevent disease, but shots to shrink tumors and stop cancer from coming back. Targets for these experimental treatments include breast and lung cancer, with gains reported this year for deadly skin cancer melanoma and pancreatic cancer.

"We're getting something to work. Now we need to get it to work better," said Dr. James Gulley, who helps lead a center at the National Cancer Institute that develops immune therapies, including cancer treatment vaccines.

More than ever, scientists understand how cancer hides from the body's immune system. Cancer vaccines, like other immunotherapies, boost the immune system to find and kill cancer cells. And some new ones use mRNA, which was developed for cancer but first used for COVID-19 vaccines.

For a vaccine to work, it needs to teach the immune system's T cells to recognize cancer as dangerous, said Dr. Nora Disis of UW Medicine's Cancer Vaccine Institute in Seattle. Once trained, T cells can travel anywhere in the body to hunt down danger.

"If you saw an activated T cell, it almost has feet," she said. "You can see it crawling through the blood vessel to get out into the tissues."

Patient volunteers are crucial to the research.

Kathleen Jade, 50, learned she had breast cancer in late February, just weeks before she and her husband were to depart Seattle for an around-the-world adventure. Instead of sailing their 46-foot boat, Shadowfax, through the Great Lakes toward the St. Lawrence Seaway, she was sitting on a hospital bed awaiting her third dose of an experimental vaccine. She's getting the vaccine to see if it will shrink her tumor before surgery.

"Even if that chance is a little bit, I felt like it's worth it," said Jade, who is also getting standard treatment.

Kathleen Jade waits to receive her third dose of an experimental breast cancer vaccine at University of Washington Medical Center–Montlake, in Seattle, on May 30, 2023. Lindsey Wasson / AP

Kathleen Jade waits to receive her third dose of an experimental breast cancer vaccine at University of Washington Medical Center–Montlake, in Seattle, on May 30, 2023. Lindsey Wasson / AP Progress on treatment vaccines has been challenging. The first, Provenge, was approved in the U.S. In 2010 to treat prostate cancer that had spread. It requires processing a patient's own immune cells in a lab and giving them back through IV. There are also treatment vaccines for early bladder cancer and advanced melanoma.

"All of these trials that failed allowed us to learn so much," Finn said.

As a result, she's now focused on patients with earlier disease since the experimental vaccines didn't help with more advanced patients. Her group is planning a vaccine study in women with a low-risk, noninvasive breast cancer called ductal carcinoma in situ.

More vaccines that prevent cancer may be ahead too. Decades-old hepatitis B vaccines prevent liver cancer and HPV vaccines, introduced in 2006, prevent cervical cancer.

In Philadelphia, Dr. Susan Domchek, director of the Basser Center at Penn Medicine, is recruiting 28 healthy people with BRCA mutations for a vaccine test. Those mutations increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The idea is to kill very early abnormal cells, before they cause problems. She likens it to periodically weeding a garden or erasing a whiteboard.

Others are developing vaccines to prevent cancer in people with precancerous lung nodules and other inherited conditions that raise cancer risk.

"Vaccines are probably the next big thing" in the quest to reduce cancer deaths, said Dr. Steve Lipkin, a medical geneticist at New York's Weill Cornell Medicine, who is leading one effort funded by the National Cancer Institute. "We're dedicating our lives to that."

People with the inherited condition Lynch syndrome have a 60% to 80% lifetime risk of developing cancer. Recruiting them for cancer vaccine trials has been remarkably easy, said Dr. Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who is leading two government-funded studies on vaccines for Lynch-related cancers.

"Patients are jumping on this in a surprising and positive way," he said.

Drugmakers Moderna and Merck are jointly developing a personalized mRNA vaccine for patients with melanoma, with a large study to begin this year. The vaccines are customized to each patient, based on the numerous mutations in their cancer tissue. A vaccine personalized in this way can train the immune system to hunt for the cancer's mutation fingerprint and kill those cells.

But such vaccines will be expensive.

"You basically have to make every vaccine from scratch. If this wasn't personalized, the vaccine could probably be made for pennies, just like the COVID vaccine," said Dr. Patrick Ott of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The vaccines under development at UW Medicine are designed to work for many patients, not just a single patient. Tests are underway in early and advanced breast cancer, lung cancer and ovarian cancer. Some results may come as soon as next year.

Research scientist Kevin Potts works on ovarian cancer cells being grown on a plastic plate at UW Medicine's Cancer Vaccine Institute Thursday, May 25, 2023, in Seattle. Lindsey Wasson / AP

Research scientist Kevin Potts works on ovarian cancer cells being grown on a plastic plate at UW Medicine's Cancer Vaccine Institute Thursday, May 25, 2023, in Seattle. Lindsey Wasson / AP Todd Pieper, 56, from suburban Seattle, is participating in testing for a vaccine intended to shrink lung cancer tumors. His cancer spread to his brain, but he's hoping to live long enough to see his daughter graduate from nursing school next year.

"I have nothing to lose and everything to gain, either for me or for other people down the road," Pieper said of his decision to volunteer.

One of the first to receive the ovarian cancer vaccine in a safety study 11 years ago was Jamie Crase of nearby Mercer Island. Diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer when she was 34, Crase thought she would die young and had made a will that bequeathed a favorite necklace to her best friend. Now 50, she has no sign of cancer and she still wears the necklace.

She doesn't know for sure if the vaccine helped, "But I'm still here."

Vaccines could be "next big thing" in cancer treatment, scientists say

New study finds AI can help improve breast cancer risk predictions

What to know about Maria Menounos' pancreatic cancer diagnosis

For uninsured people with cancer, access to care can be "very random"

What millennials need to know about colon cancer

MoreThe Next Big Advance In Cancer Treatment Could Be A Vaccine

The next big advance in cancer treatment could be a vaccine.

After decades of limited success, scientists say research has reached a turning point, with many predicting more vaccines will be out in five years.

These aren't traditional vaccines that prevent disease, but shots to shrink tumors and stop cancer from coming back. Targets for these experimental treatments include breast and lung cancer, with gains reported this year for deadly skin cancer melanoma and pancreatic cancer.

"We're getting something to work. Now we need to get it to work better," said Dr. James Gulley, who helps lead a center at the National Cancer Institute that develops immune therapies, including cancer treatment vaccines.

More than ever, scientists understand how cancer hides from the body's immune system. Cancer vaccines, like other immunotherapies, boost the immune system to find and kill cancer cells. And some new ones use mRNA, which was developed for cancer but first used for COVID-19 vaccines.

For a vaccine to work, it needs to teach the immune system's T cells to recognize cancer as dangerous, said Dr. Nora Disis of UW Medicine's Cancer Vaccine Institute in Seattle. Once trained, T cells can travel anywhere in the body to hunt down danger.

"If you saw an activated T cell, it almost has feet," she said. "You can see it crawling through the blood vessel to get out into the tissues."

Patient volunteers are crucial to the research.

Kathleen Jade, 50, learned she had breast cancer in late February, just weeks before she and her husband were to depart Seattle for an around-the-world adventure. Instead of sailing their 46-foot boat, Shadowfax, through the Great Lakes toward the St. Lawrence Seaway, she was sitting on a hospital bed awaiting her third dose of an experimental vaccine. She's getting the vaccine to see if it will shrink her tumor before surgery.

"Even if that chance is a little bit, I felt like it's worth it," said Jade, who is also getting standard treatment.

Progress on treatment vaccines has been challenging. The first, Provenge, was approved in the U.S. In 2010 to treat prostate cancer that had spread. It requires processing a patient's own immune cells in a lab and giving them back through IV. There are also treatment vaccines for early bladder cancer and advanced melanoma.

Early cancer vaccine research faltered as cancer outwitted and outlasted patients' weak immune systems, said Olja Finn, a vaccine researcher at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

"All of these trials that failed allowed us to learn so much," Finn said.

As a result, she's now focused on patients with earlier disease since the experimental vaccines didn't help with more advanced patients. Her group is planning a vaccine study in women with a low-risk, noninvasive breast cancer called ductal carcinoma in situ.

More vaccines that prevent cancer may be ahead too. Decades-old hepatitis B vaccines prevent liver cancer and HPV vaccines, introduced in 2006, prevent cervical cancer.

In Philadelphia, Dr. Susan Domchek, director of the Basser Center at Penn Medicine, is recruiting 28 healthy people with BRCA mutations for a vaccine test. Those mutations increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The idea is to kill very early abnormal cells, before they cause problems. She likens it to periodically weeding a garden or erasing a whiteboard.

Others are developing vaccines to prevent cancer in people with precancerous lung nodules and other inherited conditions that raise cancer risk.

"Vaccines are probably the next big thing" in the quest to reduce cancer deaths, said Dr. Steve Lipkin, a medical geneticist at New York's Weill Cornell Medicine, who is leading one effort funded by the National Cancer Institute. "We're dedicating our lives to that."

People with the inherited condition Lynch syndrome have a 60% to 80% lifetime risk of developing cancer. Recruiting them for cancer vaccine trials has been remarkably easy, said Dr. Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who is leading two government-funded studies on vaccines for Lynch-related cancers.

"Patients are jumping on this in a surprising and positive way," he said.

Drugmakers Moderna and Merck are jointly developing a personalized mRNA vaccine for patients with melanoma, with a large study to begin this year. The vaccines are customized to each patient, based on the numerous mutations in their cancer tissue. A vaccine personalized in this way can train the immune system to hunt for the cancer's mutation fingerprint and kill those cells.

But such vaccines will be expensive.

"You basically have to make every vaccine from scratch. If this wasn't personalized, the vaccine could probably be made for pennies, just like the COVID vaccine," said Dr. Patrick Ott of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

The vaccines under development at UW Medicine are designed to work for many patients, not just a single patient. Tests are underway in early and advanced breast cancer, lung cancer and ovarian cancer. Some results may come as soon as next year.

Todd Pieper, 56, from suburban Seattle, is participating in testing for a vaccine intended to shrink lung cancer tumors. His cancer spread to his brain, but he's hoping to live long enough to see his daughter graduate from nursing school next year.

"I have nothing to lose and everything to gain, either for me or for other people down the road," Pieper said of his decision to volunteer.

One of the first to receive the ovarian cancer vaccine in a safety study 11 years ago was Jamie Crase of nearby Mercer Island. Diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer when she was 34, Crase thought she would die young and had made a will that bequeathed a favorite necklace to her best friend. Now 50, she has no sign of cancer and she still wears the necklace.

She doesn't know for sure if the vaccine helped, "But I'm still here."

What Does A Combination Treatment Of Lung Cancer Look Like?

Lung cancer is the commonest killer among all cancers worldwide. Historically, the patients with lung cancer presented at an advanced stage, and the treatment options were limited. With rapid strides in the knowledge of the biology of this disease coupled with advancements in treatment modalities, this disease has a far better outcome now.

Almost all wings of oncology contribute to a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of lung cancer. The patient's story generally starts with seeing by a physician or a pulmonary medicine specialist who would ask for an X-ray chest and other investigations. The pulmonary physician plays a very important role in differentiating a lung cancer from tuberculosis and other lung infections that are quite common in our country. Imaging techniques like CT scan and PET scan along with a CT-guided or a bronchoscopic biopsy would confirm the diagnosis and stage of the disease.

Broadly, lung cancer can be classified pathologically as small cell and non-small cell cancers. Small cell cancers are extremely aggressive cancers, and are usually treated with chemotherapy, sometimes with radiotherapy when the disease is limited to one side of the chest, and very occasionally with surgery for a really early disease. Non-small cell lung cancers are far more common, and can be either a squamous cell carcinoma or an adenocarcinoma. The pathologist will give additional information on the targetable genetic mutations (especially in case of adenocarcinoma), and about the potential immunotherapy markers like PDL-1.

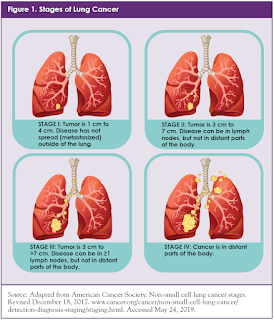

Lung cancer is generally staged based on the size and extent of the tumor in the lung, the presence of lymph nodes in the mediastinum (the space between the two lungs), and spread of disease to other sites of the body like liver, brain, bones, adrenals etc. This staging information is given by a combination of PET-CT scan and often MRI of the brain. Invasive staging for the mediastinal nodes is sometimes required, and is done by endo-bronchial ultrasound (EBUS) or by a surgical procedure called mediastinoscopy.

In early stages (Stage 1 and 2), when the disease is limited to the lung or one of its lobes, surgical removal by removal of a lobe (lobectomy) or sometimes the whole lung (pneumonectomy) is the treatment of choice. Such patients need to have further evaluation of their lung function (Pulmonary Function Test) and their cardiac function (usually by a stress Echocardiogram or a treadmill test) in order to ascertain their fitness for surgery. Traditionally, the patients would have a long cut on the side of the chest for approaching the tumor through the muscles and ribs. Today, technical developments like muscle-sparing thoracotomy, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), and robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (RATS) have made the surgery much easier to endure for the patients. The developments of stapler technology to seal and divide the blood vessels and bronchus have made the surgery much faster and safer. The advances in anesthesiology and pain management have added to the safety of surgery.

The specimen that is removed on surgery undergoes a detailed analysis by a pathologist, and the final stage of the disease and other risk factors are ascertained. Most patients will undergo adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery, unless the cancer was less than 4 cm without any other risk factor and without involvement of any lymph nodes.

The management of a patient with a locally advanced (Stage 3) disease is far more complex and nuanced. Multidisciplinary treatment has had its maximum impact in this group of patients. In Stage 3A disease (when the mediastinal nodes are limited to the side of the tumor), the patients are generally treated with chemotherapy first and then with surgery (lobectomy or pneumonectomy). Sometimes a patient with Stage 3A lung cancer may not be suitable for this approach when the mediastinal nodes are large or at multiple sites. In such patients, a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is preferred. The outcome of patient who can have surgery in addition to chemotherapy with/without radiotherapy has been seen to be better than those who cannot have surgery. Careful selection of patients for different treatment modalities is thus of paramount importance.

A patient with Stage 3B lung cancer (when the mediastinal nodes are also on opposite side, or if the tumor is involving the vital vascular structures) is usually treated by non-operative options. A combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is the standard of care in a fit individual. However, other options like chemotherapy or immunotherapy can also be considered on a case to case basis. The planning of radiotherapy and its execution is vitally important in Stage 3 patients. With the advent and growing popularity of the modern radiotherapy techniques like IMRT and IGRT, the treatment has become more focused resulting in fewer complications and improved outcome.

When the lung cancer has spread to other organs (Stage 4), the aim of treatment changes from cure to improvement in survival and control of symptoms. Very occasionally, an oligometastatic disease can be treated with curative intent including surgery when the metastasis is limited to a single site in brain or adrenal gland. In all other patients, systemic therapy is the treatment of choice. The choice of chemotherapy would depend on the type of cancer (histology), the molecular markers, the general condition of the patient, and other factors.

The outcome of such Stage 4 disease was historically quite dismal with an average survival of 9-12 months. This has undergone a paradigm shift with the understanding of new molecular mechanisms and the development of targeted drugs and immunotherapy. Especially in adenocarcinoma of the lung, if a molecular target is detected (EGFR, ALK-1, ROS-1), there are oral medications that can act on such targets. With these targeted drugs, the outcome of lung cancer has improved significantly from a dismal figure of a median survival of about 9 months to nearly 3 years.

Immunotherapy is a relatively new kid in the block, and has also had a great impact on the outcome of lung cancer. In a properly selected patient the responses to immunotherapy are sometimes quite dramatic and durable. Seeing such encouraging results of targeted therapy and immunotherapy in Stage 4 disease, these drugs are also being tested in patients with early disease in conjunction with surgery and sometimes as a replacement of conventional chemotherapy.

Most patients with lung cancer and especially those with advanced disease are often riddled with symptoms like pain and shortness of breath, and symptoms related to the site of metastasis. While the cancer-directed treatment continues, it is also vitally important to take care of these symptoms. The Pain and Palliative Medicine specialist plays a vital role in providing comfort and care to these patients.

Treatment of any cancer today is multidisciplinary, and lung cancer perfectly showcases this collaborative effort of several specialists in order to give an optimal outcome to the patient. Surgical, Medical & Radiation Oncologists work hand in hand towards the care of the patient. Specialists in Pulmonary Medicine, Nuclear Medicine, Anesthesiology & Critical Care, Pain and Palliative Care also contribute to the care of such patients. Finally, all advances in science and technology have their roots in basic research. These researchers have identified newer molecular mechanisms and targets which are employed by oncologists for use in patients with lung cancer.

Facebook Twitter Linkedin Email

DisclaimerViews expressed above are the author's own.

END OF ARTICLE

Comments

Post a Comment