Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of ...

Medications And Their Potential To Cause Increase 'Adenocarcinoma Of Prostate'

List of Drugs that may cause 'Adenocarcinoma of prostate'Advertisement

Updated on November 16, 2023 This section presents medications that are known to potentially lead to 'Adenocarcinoma of prostate' as a side effect." It's important to note that mild side effects are quite common with medications. Please be aware that the drugs listed here are individual medications and may be part of a broader combination therapy. This information is meant to be a helpful resource but should not replace professional medical advice. If you're concerned about 'Adenocarcinoma of prostate', it's best to consult a healthcare professional. In addition to 'Adenocarcinoma of prostate', other symptoms or signs might better match your side effect. We have listed these below for your convenience. If you find a symptom that more closely resembles your experience, you can use it to identify potential medications that might be the cause.Advertisement

ropinirole Find drugs that can cause other symptoms like 'Adenocarcinoma of prostate' References

↑

Adenocarcinoma: Does It Spread Very Fast?

If your doctor tells you that you have adenocarcinoma, it means you have a type of cancer that starts in the glands that line the inside of one of your organs. Sometimes it's called the "cancer of the cavities."

Adenocarcinoma can happen in many places, like your colon, breasts, stomach, esophagus (food pipe), lungs, pancreas, or prostate.

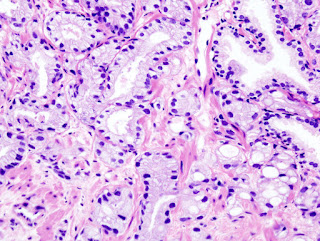

Adenocarcinoma can strike many areas of the body, including the stomach. (Photo credit: Katerina Kon/Dreamstime)

Adenocarcinoma is very common for some kinds of cancers. For instance, 99% of prostate cancers, 85% of pancreatic cancers, and 40% of lung cancers are adenocaricnomas.

It's natural to feel worried when you find out you have cancer, but remember that treatments can slow or stop the disease. You might need chemotherapy, radiation, targeted therapy, or surgery. You and your doctor will decide on the best approach, based on where your tumors are growing and how long you've had them.

Adenocarcinoma vs. Carcinoma

Cancers are classified either by the type of tissues where the cancer comes from or by the part of the body where the cancer first shows up. A carcinoma is a type of cancer that starts in the epithelial tissue. These are tissues that form the covering of all body surfaces as well as the lining of body cavities and hollow organs, and are the main tissue in glands. Most cancer cases (80-90%) are carcinomas.

Adenocarcinoma is one of the two main types of carcinoma, one where the cancer develops in an organ or gland. (The other main type, squamous cell carcinoma, occurs mostly occurs in the skin).

Your glands make fluids that your body needs to stay moist and work well. You get adenocarcinoma when cells in the glands that line your organs grow out of control. They may spread to other places and harm healthy tissue.

Adenocarcinoma can start in your:

Invasive Adenocarcinoma

If your cancer cells spread from where they originated to nearby lymph nodes (glands that are part of the immune system) or tissues, or to another part of your body, this is known as invasive adenocarcinoma.

Metastatic Adenocarcinoma

Metastatic adenocarcinoma is a later stage of invasive adenocarcinoma. If your cancer cells have spread to distant body parts, then you are considered to have metastatic adenocarcinoma. For instance, breast cancer could have spread (metastasized) to the brain or lungs.

Since adenocarcinoma can affect so many parts of the body, the causes can vary a lot. But here are some common risk factors:

The symptoms of adenocarcinoma you experience will depend on the type of cancer you have. Here are some of the main cancer symptoms:

Lung cancer

A test called low-dose CT (LDCT) scan is available for people who are smokers or otherwise at higher risk for lung cancer. Symptoms include:

Prostate cancer

If you're having regular prostate exams, this may be caught in the early stages. Otherwise, there may not be any symptoms. In later stages you may experience:

Breast cancer

If you're having regular mammograms, your doctor may catch this in the early stages. Some warning signs include:

Pancreatic cancer

There's no screening test for this and no symptoms in the early stages. In the later stages you might experience:

Stomach cancer

Screening tests are available but not given routinely in the U.S., as stomach cancer is not that common. In other parts of the world, stomach cancer screening is routine. If you have a family history of stomach cancer, ask your doctor about a screening test called an upper endoscopy (a tube with a tiny camera is put down your throat). There may be no symptoms of stomach adenocarcinoma in the early stages. In the later stages you may experience:

Colorectal (colon) cancer

If you have a regular colonoscopy, where a doctor puts a tube into your colon to check for polyps, this may be caught in the early stages. The symptoms you experience will depend on the size of the tumor in the colon but could include:

Esophageal cancer

Screening tests are available but not given routinely in the U.S. As this cancer is not that common. An upper endoscopy is the normal screening test. In the early stages, there may be no symptoms. In later stages, symptoms may include:

Your doctor will give you a physical exam. They may feel your organs to see if there is any swelling or a growth.

They may also notice something's not right when you have regular screening tests like a colonoscopy or a mammogram.

You may also get tests to see if you have adenocarcinoma in any of your organs:

Adenocarcinoma grading

This refers to the grade given to your cancer cells based on what they look like under a microscope, compared with normal cells. If the tumor cells look like normal cells (well-differentiated), they are given a low grade. If they don't look very much like normal cells (poorly differentiated), they are given a high grade. The higher the grade, the faster the cancer is likely to spread. Grades are usually from 1 to 4, though some may only go from 1 to 3. The grades might also be written in Roman numerals.

Grade 1. Well-differentiated; cancer cells not growing very fast

Grade 2. Moderately differentiated; cancer cells growing faster than normal cells

Grade 3. Poorly differentiated; cancer cells growing and spreading fast

Grade 4. Undifferentiated; cancer cells growing and spreading fast

Grade X. Grade is unknown.

Adenocarcinoma staging

This shouldn't be confused with grading. Grading has to do with the appearance of the cancerous cells, while staging describes the size of the cancer tumor and how far it has spread. There are four stages usually designated as numbers 1 to 4, or as Roman numerals I to IV. The higher the number, the more advanced the cancer is. Each type of cancer has its own staging system, but here is the general rule:

Stage I. The cancer is small and hasn't spread beyond the cells where it started.

Stage II. The cancer is a bit larger than at stage I but hasn't spread beyond the organ where it started.

Stage III. The cancer is larger than stage II and may have spread to nearby lymph nodes or other tissues.

Stage IV. The cancer has spread to at least one other organ (metastasized).

You might see a stage 0 as well. This means there is no cancer but abnormal cells have been found with the potential to become cancerous. These should be treated as well.

The staging number helps the doctor decide how to treat the cancer. Higher-stage cancers are harder to treat than lower-stage cancers.

TNM Staging System

This system uses letters to describe the kind of cancer you have:

T (tumor) describes the size of your tumor, using numbers 1-4 (1 is small; 4 is very large).

N (nodes) describes how many of your lymph nodes have cancer, using numbers 1-3. (1 means no lymph nodes have cancer; 3 means many do).

M (metastases) describes whether your cancer has spread to other parts of your body (0 means it has not spread; 1 means it has spread).

You might see your cancer described as (for instance) T2N1M0 in a lab report. If you see an X included (for example T2N1MX), that means that something cannot be measured. In this example, the metastases cannot be measured.

Your treatment depends on the type of adenocarcinoma you have and the stage of your cancer.

You may need chemo along with surgery and radiation to treat your cancer.

Your cancer treatment can have side effects. You might get very tired or feel like you need to throw up. Your doctor can suggest ways to manage these problems. They may prescribe drugs that fight nausea.

Talk to your family and friends about how you're feeling, and don't hesitate to ask them for help while you're getting treatment. Also tell them about your worries and fears. They can be a huge source of support.

Check the web site of the American Cancer Society. You can find out about local support groups, where you'll meet people who have the same type of cancer as you and can share their experience.

Adenocarcinoma is a very common type of cancer that starts either in the skin or in one of the body cavities. It can affect many parts of your body like your colon, breasts, lungs, pancreas, or prostate. Treatments like surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy can stop or slow down the disease.

Is adenocarcinoma cancer curable?

Yes, in many cases. The survival rate for adenocarcinoma depends on the type of cancer, stage, and where it is located. The relative survival rate tells you what percentage of people who have the same type and stage of cancer are still alive 5 years after diagnosis. The figures below are based on research in the U.S.

However, a lot depends on the type of cancer. More than 99% of people with prostate cancer were alive 5 years later. Some 90% of people with breast cancer or colorectal cancer were alive 5 years later. On the other hand, only 32% of people with stomach cancer and only 7% of those with pancreatic cancer were alive 5 years later. Early detection (thanks to routine screening tests) has a lot to do with high survival numbers.

How serious is adenocarcinoma?

It depends on the type of cancer you've been diagnosed with and how far along it was when diagnosed. Some adenocarcinomas are more serious than others.

Behind The FDA Approval Of Enzalutamide For Prostate Cancer

Neal Shore, MD, FACS, discussed the phase 3 EMBARK trial and what the FDA approval of enzalutamide means for the prostate cancer treatment landscape.

PC-3 human prostate cancer cells: © heitipaves - stock.Adobe.Com

The FDA approved enzalutamide (Xtandi) for the treatment of nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence at high risk for metastasis on November 16, 2023.1

Enzalutamide, an androgen receptor signaling inhibitor, is the first of its kind to be approved in this intent-to-treat (ITT) population in combination with the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) leuprolide.

Findings from the phase 3 EMBARK trial (NCT02319837) supported this approval. Neal Shore, MD, FACS, the trial's primary investigator, discussed the importance and implications of the findings.

"Historically, up until the results of EMBARK, we didn't have [the] highest level of evidence—what we refer to as level 1 evidence—for how to best or optimally treat patients with high-risk biochemical recurrence. Those are the patients who've had prior surgical prostatectomy, radiation, or both. Some might even argue we were doing our decision-making from the seat of our pants," said Shore, United States chief medical officer of surgery and oncology, GenesisCare USA, and director of the Carolina Urologic Research Center, in an interview with Targeted OncologyTM.

"This was a remarkably successful study because both therapeutic arms, the combination of LHRH and enzalutamide, as well as the monotherapy enzalutamide with no testosterone suppression, both bested monotherapy LHRH-agonist [androgen deprivation therapy]. That was what's so compelling about the trial," Shore said.

About the FDA Approval of EnzalutamideThe EMBARK trial met its primary end point of metastasis-free survival (MFS) with a statistically significant improvement with enzalutamide plus leuprolide vs placebo plus leuprolide, and the median was not reached for either arm (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.30-0.61; P <.0001) at a median follow-up of 60.7 months. Enzalutamide monotherapy also had a statistically significant improvement in MFS compared with placebo and leuprolide (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.46-0.87; P =.0049). Risk of prostate specific antigen (PSA) progression was also reduced in the combination enzalutamide/leuprolide arm (HR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.03-0.14; P <.0001) and enzalutamide monotherapy arm (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.23-0.49; P <.0001).1,2

"Very importantly, we don't have our final overall survival data yet," Shore said. "Our primary end point, which was metastasis-free survival, was met in both the combination LHRH and [enzalutamide] arm, as well as in the enzalutamide monotherapy arm. We bested monotherapy LHRH for the metastasis-free survival primary endpoint and therefore, [it was] a full-on successful trial. The overall survival is clearly trending in favor of both the combination beating monotherapy LHRH and the monotherapy [enzalutamide]."

About the Phase 3 EMBARK TrialThe randomized phase 3 EMBARK trial assessed enzalutamide plus leuprolide in the ITT population. Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 fashion to receive either 160 mg of enzalutamide orally with leuprolide as a subcutaneous or intramuscular injection every 12 weeks, 160 mg of oral enzalutamide monotherapy, or leuprolide injection with oral placebo.3

"All of the investigative sites globally in Asia, Europe, South America, [and] North America we were able to enroll over 1000 patients and look at direct comparisons in a prospective way. If we added enzalutamide, the most well-studied androgen receptor pathway inhibitor in the class, having been approved now and on the market globally for over 10 years, and demonstrated its efficacy throughout the continuum of prostate cancer, starting from hormone sensitive metastatic all the way through resistant disease, could we combine that with traditional LHRH therapy and compare it [with] LHRH therapy alone…to see which one did better?" Shore said.

The study's primary end point was MFS. The secondary end points included overall survival, time to castration resistance, composite of safety, time to PSA progression, time to first use of new antineoplastic therapy, and time to distant metastasis.

Patients were considered eligible to participate in the trial if they had histologically or cytologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma without neuroendocrine differentiation, signet cell, or small cell features. Patients were also required to have received initial treatment by radical prostatectomy and/or radiotherapy, have a PSA doubling time ≤ 9 months, and a serum testosterone ≥ 150 ng/dL (5.2 nmol/L). Patients were not eligible to participate if they had prior or present evidence of distant metastatic disease, received prior hormonal therapy, or received prior cytotoxic chemotherapy.

"We had 2 different regimens being pitted against [each other]. [There was] the commonly utilized therapy, LHRH monotherapy, and we enriched the patient population for patients who were at high-risk, meaning their doubling times were less than or equal to 9 months," Shore added.

Next StepsEnzalutamide's expanded approval comes with excitement, but the work on the EMBARK trial is far from over.

"We expect that sometime in 2025, we'll have enough events, and we will be reporting back on the overall survival. Many of our colleagues say, 'Yes, I liked and I understand the metastasis-free survival endpoint, [but] I still want to see overall survival.' That didn't prevent the FDA from granting the expanded label, which I think was great," Shore added.

Shore also emphasized the need for more in-depth analyses of patient outcomes.

"How do you make the decision between monotherapy [enzalutamide] vs the combination LHRH/[enzalutamide]. We presented patient-reported outcome sexual function data at [the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress] 2023 this year, and we published that simultaneously in [the New England Journal of Medicine] evidence. We found was there's clearly, for the monotherapy [enzalutamide] in patients. They have an improvement in their sexual function, but we need to look deeper into that, and we need to do some additional prospective studies with further analyses and questionnaires," Shore said.

"The bottom line is, this is a real step forward and an advancement in our therapeutic armamentarium to have that important patient-physician shared decision making where we now have option better options for patients," Shore concluded.

REFERENCES: 1. FDA approves enzalutamide for non-metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer with biochemical recurrence. News release. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. November 17, 2023. Accessed November 21, 2023. Https://tinyurl.Com/yc8b5str 2. Shore ND, de Almeida Luz M, De Giorgi U, et al. LBA02-09 EMBARK: a phase 3 randomized study of enzalutamide or placebo plus leuprolide acetate and enzalutamide monotherapy in high-risk biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. J Urol. 2023;210(1):224-226. Doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003518 3. Safety and efficacy study of enzalutamide plus leuprolide in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer (EMBARK). ClinicalTrials.Gov. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed November 21, 2023. Https://www.Clinicaltrials.Gov/study/NCT02319837

Comments

Post a Comment