Prostate cancer: recognition and diagnosis - The Pharmaceutical Journal

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

Prostate cancer is the fourth most diagnosed cancer worldwide, representing 7.3% of all new cases, preceded only by breast, lung and colorectal cancer[1].

In 2017, there were around 48,600 new cases of prostate cancer in the UK, making it the most common cancer in men, and data also show that it represents 26% of all new cancers in males[2,3]. Incidence rates in the UK are projected to rise by 12% by 2035 to 233 cases per 100,000 males[2]. This can be attributed to lifestyle changes, such as diet and decrease in UV exposure linked with vitamin D deficiency, but also to a better understanding and use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as a screening tool[4].

In 2020, prostate cancer accounted for 7% of all cancer deaths (around 11,900) and 13% of cancer deaths in males in the UK[2]. Mortality rates for prostate cancer are projected to fall in the UK by 16% by 2035, to 48 deaths per 100,000 males[5]. This can be attributed to an increase in prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing, improvement in therapy, including the use of androgen receptor targeted agents, such as abiraterone and enzalutamide, and technological advances in surgery and radiotherapy[6].

Prostate cancer tends to develop slowly, and signs or symptoms may not present for many years[7]. Men with prostate cancer will survive for five years or more when it is diagnosed at its earliest stage, compared with around 50% surviving for five years or more when diagnosed at a later stage[2].

Pharmacists should be aware of the red flags for prostate cancer, as they may be discussed as part of a routine medicines review or a patient may present directly with indicative symptoms seeking advice. Pharmacists should also be confident to refer the patient to their GP if any symptoms are of concern.

This article provides an overview of prostate cancer, including early detection and prevention, PSA testing, diagnosis and staging for pharmacists, particularly those in primary care.

The prostate gland

The prostate is a small gland in the pelvis, located underneath the bladder, surrounding the urethra and in front of the rectum and is part of the male reproductive system[8].

Semen is comprised of sperm cells that originate in the testis and fluids from surrounding glands, including the prostate. In addition to this, the prostate has muscles that ensure the semen is pressed against the urethra allowing its release during ejaculation. To facilitate this process, the prostate also produces a protein called PSA that is responsible for making the semen more fluid and therefore easier to expel[9].

The prostate also has a role in converting the main male sex hormone, testosterone, into dihydrotestosterone, the activated form of the hormone[9].

The prostate gland is the size of a walnut, but with age tends to become bigger. Enlarged prostates can squeeze the urethra, which may cause disruptions when passing urine[10].

Risk factors and prevention

The causes of prostate cancer are not yet fully understood; however, several factors are known to increase the risk of developing the disease. These include:

- Older age: More than half of prostate cancer cases occur in men aged over 70 years. In white men with no family history of prostate cancer, the risk of developing the disease increases after the age of 50 years, and over the age of 40 years for black men or those with a first degree relative affected by the disease[11];

- Ethnicity: Research shows that black men are twice as likely to be diagnosed and die of prostate cancer than white men. The same ratio applies to white men when compared to Asian men[12]. It is thought that African and African-Caribbean men have a genetic susceptibility that places them at a higher risk of developing prostate cancer and developing more aggressive prostate cancer[13,14]. A variety of genes have been identified but their impact on the observed differences appear small. The genes that have been located are predominantly involved in promoting androgen metabolism, enabling uncontrollable prostate growth and providing a driving force for prostate cancer initiation and progression[15];

- Family history: Those who have a first degree relative with prostate cancer see their risk increased by around 2.1–2.8 times; this risk increases to 3.5 times when two relatives presented with the disease[16];

- High body mass index (BMI): A BMI of 25 to 29.9 is considered overweight. A BMI of 30 and above is considered obese[17];

- Inflammation of the prostate: (also known as prostatitis)[18];

- Lifestyle: smoking and lack of exercise can increase the risk of prostate cancer; studies have shown conflicting evidence for the role of diet[19].

The most significant risk factors for developing prostate cancer (age, ethnicity and family history) are out of a patient's control. While there is no way to prevent prostate cancer, pharmacists and pharmacy teams are in a position to offer patients advice and promote the following interventions that may help reduce the risk of prostate cancer in the absence of other risk factors. This can happen during a medicines use review consultation or when approached by the patient for advice.

- Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight: The ideal diet for prevention of prostate cancer, or any other cancer, is still the subject of much debate. Currently, there is no evidence for specific recommendations, but the following general principles should be advised: increase consumption of fruit and vegetables; replacement of refined carbohydrates with whole grains; reduce the intake of fat (especially saturated); and reduce the consumption of processed meat[20];

- Keeping physically active: It is important to stay active, regardless of the type of exercise the patient chooses. For patients taking hormonal treatments, the practice of resistance exercise (e.g. weightlifting) can help with the bone thinning side effect of those therapies. The recommendation is to exercise at least 2–3 times a week. The time spent doing it will depend on the patient level of fitness and could start as 10–15 minute sessions[21].

Symptoms

Prostate cancer usually develops slowly, and many men do not experience symptoms until the prostate gland is large enough to impact the urethra[22]. Once this occurs, men may experience:

- Increased urinary frequency;

- Having to strain when urinating;

- An inability to completely void the bladder[22].

These symptoms should not be ignored; however, they are not specific to prostate cancer. Other associated pathologies include:

- Acute bacterial prostatitis — an infection that causes pelvic pain and urinary tract symptoms such as dysuria, urinary frequency and urinary retention, and may lead to systemic symptoms (e.g. fever);

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) — an increase in size of the prostate gland;

- Non-bacterial prostatitis — persistent pain in the area around the prostate gland;

- Tuberculosis of the genitourinary system[23].

If the prostate cancer has spread outside the prostate — as in locally invasive, advanced or metastatic prostate cancer — other symptoms may also be present, such as:

- Erectile dysfunction;

- Back, hip or pelvic pain;

- Blood in the urine/semen;

- Unexplained weight loss[24].

If a patient presents to community pharmacy with any of the symptoms above, they should be advised to see their GP promptly.

Diagnosis

Patients presenting to their GP with symptoms that suggest prostate cancer (e.g. nocturia, urinary frequency, hesitancy, urgency, retention, erectile dysfunction or visible haematuria) will be asked for a urine sample to exclude possible infection, before being offered a blood test to check the PSA result. Patients who have had a urine infection should not undergo a PSA test for at least a month after treatment finishes, as they can cause a transient increase in serum PSA[25]. The GP may also recommend a digital rectal examination (DRE) to assess the size of the prostate[26].

There is no single PSA level that is considered 'normal' as it varies from man to man and the normal level increases with age. As a guide, men in their 50s should have further investigations if they present with a PSA result above 3ng/mL, in their 60s above 4ng/mL and in their 70s above 5ng/mL. There are no PSA limits for men aged over 80 years[27].

If the PSA test result is outside these ranges and a hard, irregular prostate is felt on DRE, the patient should be referred to a hospital urologist urgently via the 'suspected cancer pathway referral' and should be seen within two weeks[28].

In asymptomatic patients, if the PSA result is borderline, the test should be repeated after around four weeks. If the result still shows that the PSA is rising, then a referral to the urology team should be made as described above[29].

At present, men aged 50 years and over can request a PSA test from their GP. However, the associated risks (e.g. unnecessary biopsies and treatments that might follow a false positive) must be discussed with the GP beforehand. Based on the latest review performed by the UK National Screening Committee, Public Health England decided that PSA testing is not accurate enough to meet the requirements of a national screening programme[30].

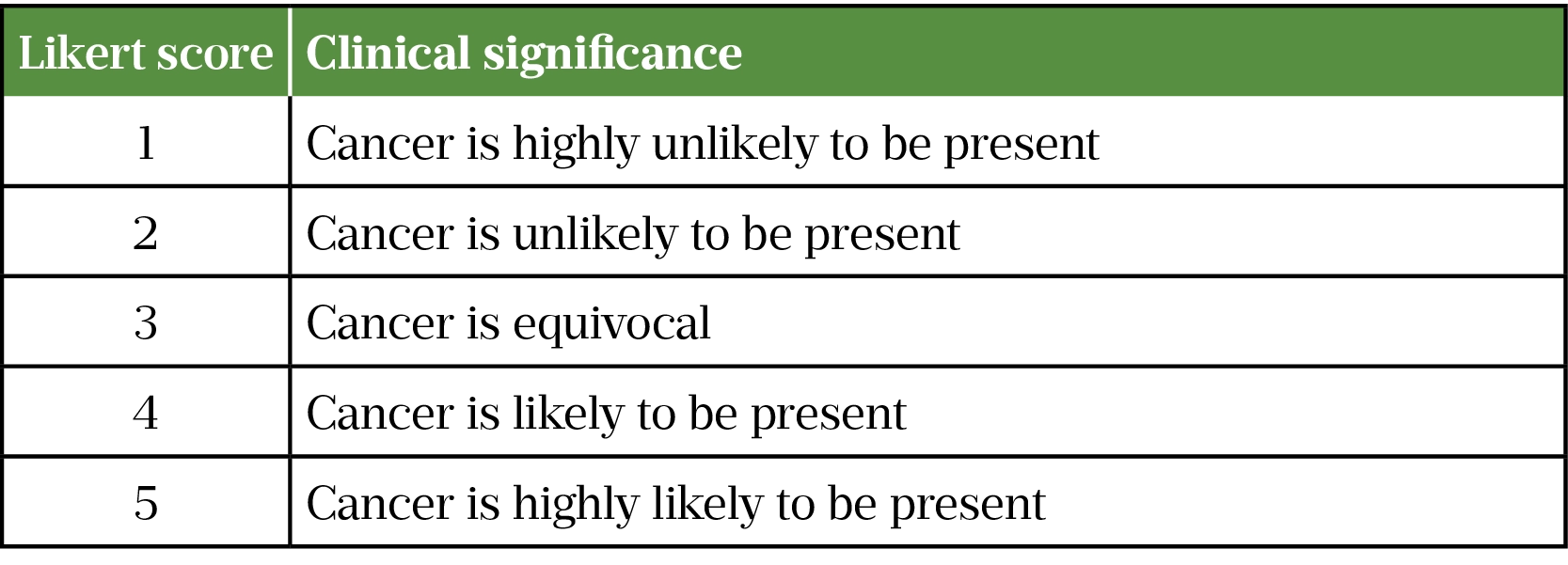

On referral to a hospital urologist, a pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan will be performed to identify the presence of any cancer and, depending on the results, the patient may be referred for a biopsy[3]. On that scan the radiologists will assign a Likert score (see Table 1). NICE recommends that a biopsy should be offered to those with a Likert score of 3 or more. For those patients with a lower Likert score, a biopsy should only be offered after discussing risks/benefits with the patient. It should be explained to the patient that there is a small chance that a low-risk MRI will actually develop significant cancer and that some treatments work better in early disease, but that the biopsy may not actually find disease. The findings may indicate a clinically insignificant form of prostate cancer (unlikely to have any life-threatening consequences) that will lead to follow ups and treatment, associated anxiety and finally the complications associated with an invasive medical procedure (e.g. urinary retention, rectal bleeding)[24].

The most frequent type of biopsy performed is transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy — or 'TRUS' — which uses imaging guidance to insert a needle into the prostate, via the rectum, under local anaesthetic, to obtain the tissue sample[31].

A multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) is useful in identifying lesions before biopsy — if this result is positive then there is indication to perform a targeted and/or a systemic biopsy, however if the mpMRI is negative and the risk of prostate cancer is low, a biopsy does not need to be performed[32]. If the presence of a lesion is confirmed, further tests will be performed to determine the stage and extent of the tumour.

Staging

The investigations performed allow clinicians to understand how the cancer has progressed and to classify it according to relevant criteria.

Cell type and origin

Prostate cancer can be classified based on the origin of affected cells:

- Acinar adenocarcinoma is the most common, accounting for nearly all cases of prostate cancer — it originates from the cells lining the prostate gland;

- Ductal adenocarcinoma is more aggressive and originates from the cells lining the ducts of the prostate gland;

- Transitional cell cancer originates from the urethra[33].

In terms of location, prostate cancer is classified as localised when it is confined to the prostate gland, locally advanced when it is has elapsed the prostate gland and is established in the nearby surrounding tissues and lymph nodes, and advanced when it has spread to other distant sites, also known as metastatic prostate cancer[34].

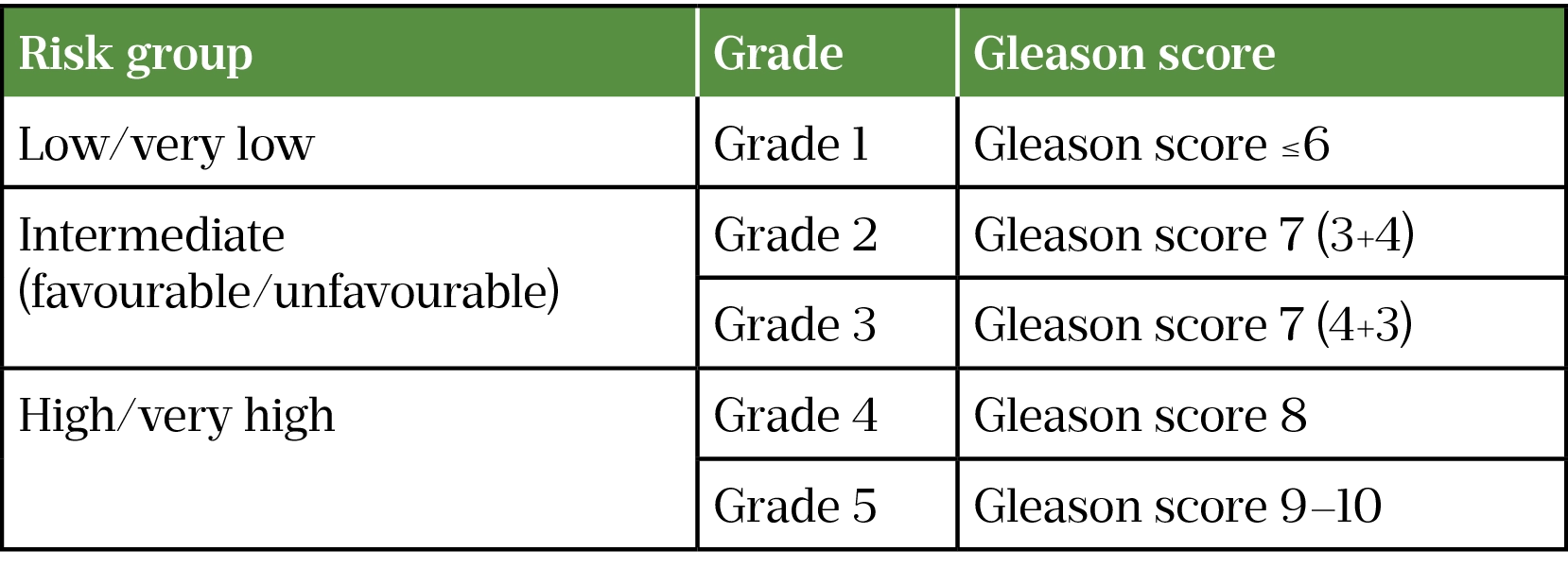

Gleason Score and grade

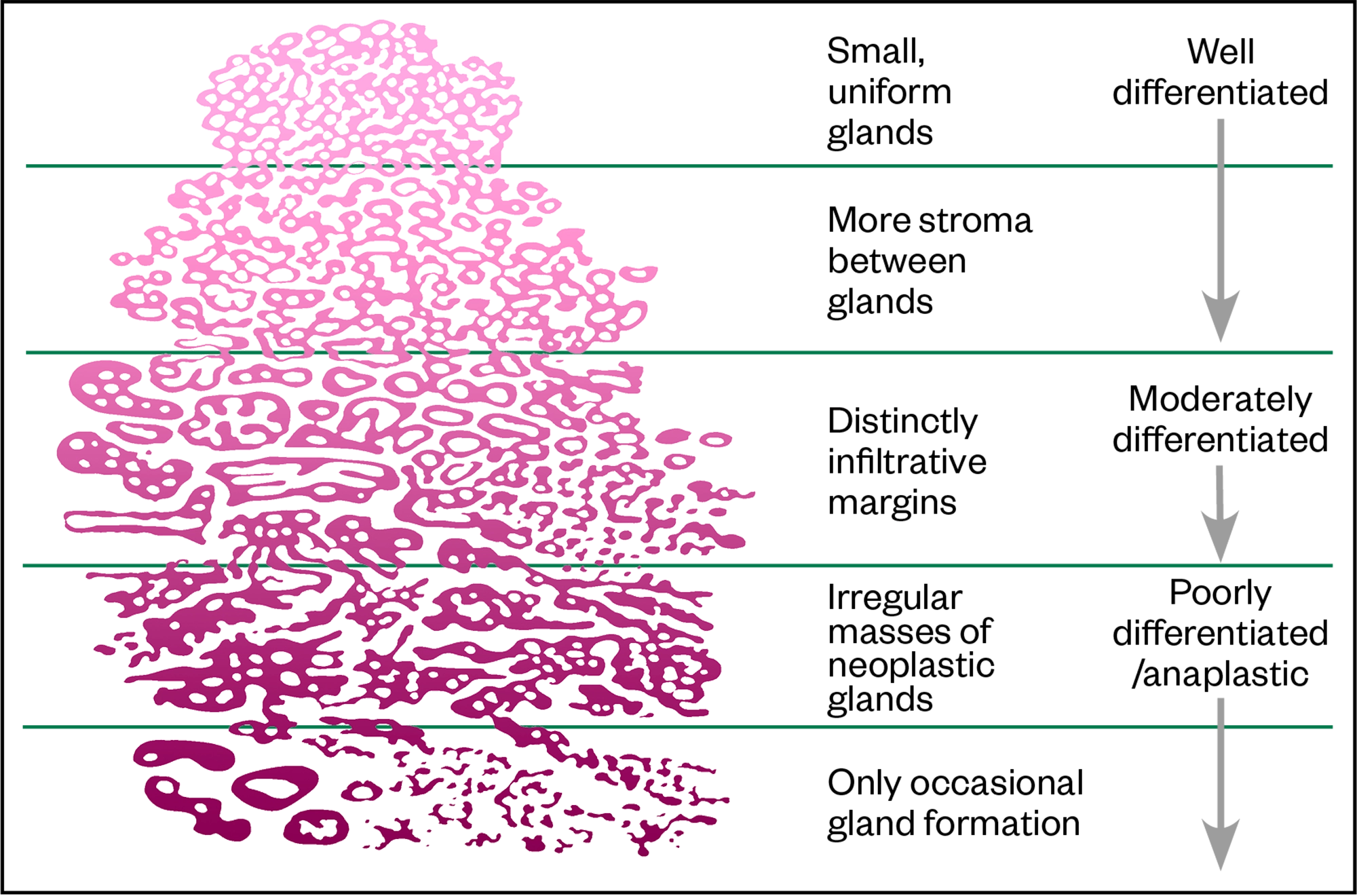

The Gleason Score describes how closely the cells of the biopsy sample resemble the normal prostate tissue. The score runs from 1 (most similar) to 5 (more differentiated) (see Figure). The two most representative areas of the sample are chosen, and a score is given based on the cells (e.g. 4+5)[35]. This allows clinicians to classify the tumour grade and risk (see Table 2)[36].

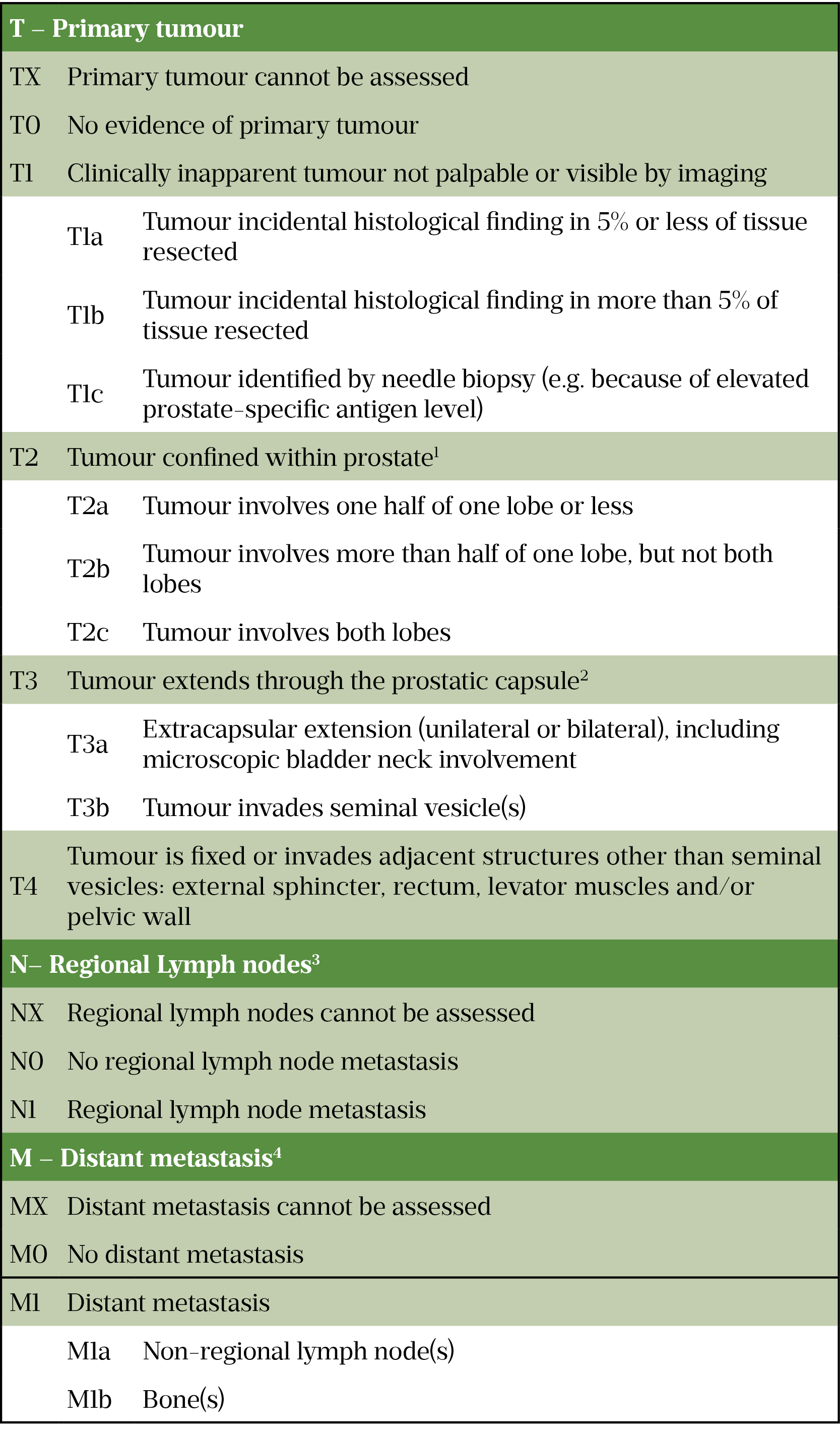

TNM staging

Developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer, TNM staging is used to determine the size of the cancer and whether it has spread[37]. 'T' refers to the size of the tumour, 'N' refers to the presence of disease in the lymph nodes and 'M' refers to metastasis[38]. Table 3 outlines how this information is categorised.

Barriers to diagnosis and the role of the pharmacist

Given that early diagnosis of prostate cancer can lead to significantly better health outcomes, it is unfortunate that there are barriers to men seeking medical advice[2]. In the UK, men of African and African-Caribbean descent are twice as likely to get prostate cancer as white men of the same age[39].

Pharmacists should be mindful that ethnicity is an important risk factor and provide information about prostate cancer screening to these patients if appropriate.

Men tend to have several general concerns and beliefs that prevent them from seeking advice about prostate cancer. These include believing that seeking information about health is not masculine, being embarrassed about being diagnosed with a male-specific disease, and thinking that men do not necessarily pursue information about cancer[40]. They may also have a fear of examinations and tests, such as DRE[41].

These attitudes and beliefs — together with asymptomatic presentation in early stages and men having poor awareness of symptoms, awareness of their own risk and knowledge of the benefits of treatment — all impact the likelihood of men seeking advice from healthcare professionals[40].

Pharmacists in primary care should therefore:

- Consider referring patients to their GP if they are asking about urinary symptoms (e.g. increased frequency, urinary urgency, poor urinary flow, pain on urination or ejaculation or blood in urine or semen), especially if they have risk factors for prostate cancer. While prostate cancer does not always present with urinary symptoms, a GP will be able to rule out other causes;

- Identify high-risk patients who may benefit from PSA testing (e.g. patients aged over 50 years, family history of prostate cancer or men of African and African-Caribbean descent) and encourage them to speak to their GP;

- Reassure patients that symptoms may be related to benign conditions (BPH, prostatitis, UTI), but if it is prostate cancer there are several effective treatments available and early diagnosis is often associated with a good prognosis;

- Give patients advice about how to speak to their GP and ask for a PSA test if needed. For example, explain to patients why they may be at increased risk of prostate cancer and why they may benefit from a PSA test, so that they feel more confident requesting a test. The Prostate Cancer UK leaflet 'Understanding the PSA test' can be recommended to patients;

- Allay patient concerns about tests and procedures, especially procedures such as DRE;

- Participate in local and national patient awareness campaigns and those that encourage patients with risk factors for prostate cancer to get a PSA test;

- Provide diet and lifestyle advice, where appropriate;

- Provide appropriate booklets and fact sheets to patients so they can read them in their own time before speaking to their GP. Prostate Cancer UK have a plethora of excellent, easy to read resources that can be ordered in print free of charge or downloaded for patients. These materials can be accessed on the Prostate Cancer UK website

1

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.216604

Rawla P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J Oncol 2019;10:63–89. doi:10.14740/wjon11915

Smittenaar CR, Petersen KA, Stewart K, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer 2016;115:1147–55. doi:10.1038/bjc.2016.3046

Carioli G, Bertuccio P, Boffetta P, et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2020 with a focus on prostate cancer. Annals of Oncology 2020;31:650–8. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.00912

Bokhorst LP, Roobol MJ. Ethnicity and prostate cancer: the way to solve the screening problem? BMC Med 2015;13. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0427-z13

Wu I, Modlin CS. Disparities in prostate cancer in African American men: What primary care physicians can do. CCJM 2012;79:313–20. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.1100114

Ben-Shlomo Y, Evans S, Ibrahim F, et al. The Risk of Prostate Cancer amongst Black Men in the United Kingdom: The PROCESS Cohort Study. European Urology 2008;53:99–105. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.04715

Chornokur G, Dalton K, Borysova ME, et al. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate 2010;71:985–97. doi:10.1002/pros.2131416

Ang M, Borg M, et al. Survival outcomes in men with a positive family history of prostate cancer: a registry based study. BMC Cancer 2020;20. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-07174-920

Lin P-H, Aronson W, Freedland SJ. Nutrition, dietary interventions and prostate cancer: the latest evidence. BMC Med 2015;13. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0234-y32

Parker C, Castro E, Fizazi K, et al. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 2020;31:1119–34. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.01133

DeVita V, Lawrence T, Rosenberg S. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's cancer: Principles & practice of oncology. 10th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health Adis 2015.

39

Steinberg GD, Carter BS, Beaty TH, et al. Family history and the risk of prostate cancer. Prostate 1990;17:337–47. doi:10.1002/pros.299017040940

Ettridge KA, Bowden JA, Chambers SK, et al. "Prostate cancer is far more hidden…": Perceptions of stigma, social isolation and help-seeking among men with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care 2017;27:e12790. doi:10.1111/ecc.12790

Comments

Post a Comment